Introduction to Commentary by Gregory of Nyssa on the Lord's Prayer

By Father T. StylianopoulosDownload pdf

“Prayer is equality with angels, progress in good things,overthrowing evil, correction of sinners, enjoyment of present gifts, assurance of future blessings.”

St. Gregory of Nyssa

"Lord, teach us to pray," asked one of Jesus’ disciples according to the Gospel of Luke (11:1). Jesus’ answer was the Lord's Prayer, a unique and priceless treasure from the lips of the Master. The uniqueness of the Lord's Prayer is not only that it is a gift of Christ but also that it reflects, in spirit and content, the great themes of what Jesus taught and lived. From each of its petitions according to St. Mat- thew's full version of the Lord's Prayer (Mt 6:913), we can virtually outline the key themes of Christ's ministry -- the personal fatherhood and holiness of God, the proclamation of God's kingdom and will, the concern for daily human sustenance, the plea for forgiveness from God and from one another, as well as the entreaty for protection from temptations and deliverance from the wiles of Satan. In the words of Tertullian1, a second century Chris- tian teacher, the Lord's Prayer is a "summary of the gospel." In the ancient Church, as shown by the Greek title of St. Gregory of Nyssa’s work, the Lord's Prayer was called simply "the Prayer."

Being a model prayer that claims Christ himself as its author, the Lord's Prayer has enjoyed a position of prominence in the life and thought of Christians throughout the ages. Christians pray the Lord's Prayer morning and night in their personal devotions. The prayer is frequently heard in liturgical services and other Christian gatherings. It is no wonder therefore that it has drawn the attention of many ancient and modern interpreters. We might say that our very familiarity with the prayer has often dulled the sensibilities of Christians to its meaning and power. It has also challenged Christian lead- ers to take up the task of teaching the Lord's Prayer, interpreting each of its petitions and applying them to the ordinary life of Christians. Such is the case with St. Gregory (160 - 225) of Carthage. Converted to Christianity about 197–198. He is perhaps most famous for coining the term Trinity (Latin trinitas) and giving the first exposition of the formula. Tertullian was trained as a lawyer in Rome. He returned to Carthage, where he wrote for over twenty years in defense of the Chris- tian faith. Later in life, Tertullian became frustrated with the laxity of his Orthodox brethren. He left the church in 213 and joined a prophetic movement known as Montanism which was condemned by the Church. of Nyssa. He wants both to expound the meaning of the Lord's Prayer in the context of daily life, as well as to convince Christians of the value of prayer as an intrinsic aspect of Christian life and spirituality.

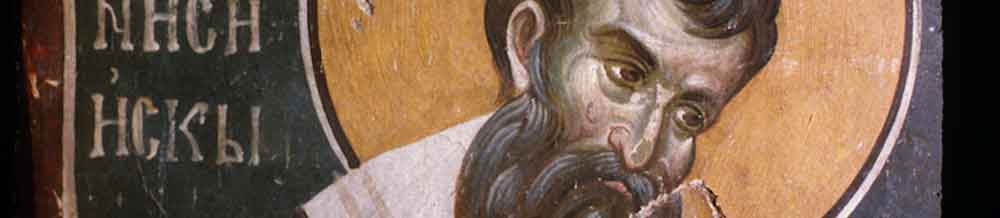

A few words about the life of St. Gregory may be helpful. Born to a wealthy and noble family, St. Gregory (335-394 AD) was the younger brother of St. Basil the Great (330- 379). Their father was a prominent rhetorician in Ceasarea, Asia Minor, a profession that both Basil and Gregory initially pursued. Gregory was one of ten children, three of whom became bishops (Basil, Gregory and Peter). By his own account, Gregory's teachers were not only St. Basil, but also an exceedingly gifted and saintly sister, St. Macrina, who was a theologian in her own right. Although ascetic minded, it is likely that St. Gregory was married. He served as bishop both at Nyssa (371-379) and for a while at Sebaste (380), towns in Asia Minor.

A brilliant theological and philosophical mind, St. Gregory is known as one of the three great theologians of the Church, the three Cappadocians, along with St. Basil and their mutual friend St. Gregory of Nazianzus, surnamed the Theologian. St. Gregory of Nyssa took an active part in the

theological controversies of that age, including the Second Ecumenical Council in Constantinople (381). After the Second Council he was acknowledged as a standard-bearer of Ortho- doxy in his geographical area. He also wrote many doctrinal ind pastoral works, includ- ing the present one on the Lord's Prayer. His prominence was such that, among other things, he was chosen to give the funeral oration for Empress Pulcheria (385). St. Gregory died around 394.

It is not known when St. Gregory composed his work on the Lord's Prayer. The Greek title in the manuscripts is simply Eis ten Proseuchen ("On the Prayer"). The work con- sists of five homilies (logoi), written in literary fashion and apparently delivered to some Christian gathering. I have chosen to call them discourses because of their literary character. The First Discourse deals with the nature of prayer - why we need to pray, what is prayer, prayer as an expression of thanksgiving to God, about not babbling in prayer by means of foolish requests, and how we should understand the Old Testa- ment prayers against enemies. The reader will find a rich cluster of spiritual insights about how prayer prevents sin from entering the soul, about being thankful and asking for things appropriate to the dignity of God, about the danger of greed always leading people to pursue more and more of something, about how God draws us like children from material to spiritual blessings, about how we should pray against the real ene- mies, that is, all expressions of evil and the demons, not against human beings them- selves. St. Gregory has an extended and eloquent definition of prayer which in part reads: "Prayer is the seal of virginity, the fidelity of marriage, the weapon of travelers, the guardian of those sleeping, the courage of those awake ... Prayer is to speak with God, to behold invisible realities, to satisfy spiritual yearning. Prayer is equality with angels, progress in good things, overthrowing of evil, correction of sinners, enjoyment of present gifts, assurance of future blessings."

In his Second Discourse St. Gregory interprets the invocation "Our Father who art in heaven." Comparing Moses and Christ, St. Gregory exalts the superiority of the grace and power of Christ who through the words of the Lord's Prayer leads us "to the knowledge of the ascent to God achieved through a spiritual way of life." The vision of ascent to God through the knowledge of the grace and teachings of Christ is the key to St. Gregory's spirituality and, as well, to his interpretation of the Lord's Prayer. The fo- cal issue for him is our identity as Christians, our authenticity as children of God in Christ, brought to the Father by Christ, and taught by Christ to call Him Father. Using startling imagery and uncompromising language, St. Gregory states that the qualities of our lives -- whether they are goodness, holiness, and mercy or hatred, slander, and greed -- show whom we invoke when we say "Father." Do we truly invoke God or the Devil? Gregory's sharp pen is then softened by a lyrical meditation on the prodigal son as an example of how a sinner can return to his spiritual homeland and become a true son or daughter of God. Since God has already made all the necessary provisions for our salvation, all that is necessary is a free and firm resolve to return to the home of our heavenly Father.

The Third Discourse on "Hallowed be Thy Name, Thy Kingdom come" begins with an allegorical interpretation of the vestments of the high priest in the Old Testament. For St. Gregory, the symbolic meaning of these vestments is to be found in the gifts and virtues which Christ bestows on his followers, and which ought to be exemplified es- pecially by the ordained priests of the Church. The same spiritual adornments are the means by which God's Kingdom is powerfully manifest among people, and His Name is sanctified and glorified in the world, just as Christ taught in the Sermon on the Mount when He said: "Let your light shine before people, that they may see your good works and give glory to your Father who is in heaven" (Mt 5:16). St. Gregory is realistic about the spiritual warfare that Christian life involves. Human life is engulfed by evil. Sin eve- rywhere abounds. Death rules over all as a merciless tyrant. Sweet therefore is the voice that fervently prays to God, "Thy Kingdom come." When God's Kingdom comes by the power of divine grace, all opposing evils "collapse into nothingness," says St. Gregory. "Darkness cannot endure the presence of light. Sickness cannot exist when health returns. The evil passions are not active when freedom from passions takes hold. When life reigns in our midst and incorruption holds sway, gone is death and van- ished is corruption."

In the Divine Liturgy and other prayers of the Church, Christ is called the "Physician" of our souls and bodies. The Church Fathers have often spoken of salvation as therapy -- a process from a state of sickness to a state of health. It is around this imagery that St. Gregory develops his Fourth Discourse in which he closely connects the two petitions about God's will and daily bread. As a result of disobedience to the divine will, the hu- man condition is defined by a state of sickness marked by all manner of evil, distrac- tions, illusions, false pursuits, and suffering on earth. To pray that God's will be done on earth is to invite the power of the divine will to lead us to a state of health reflecting the life of heaven -- love, purity, justice, holiness, and goodness. While God is almighty and always ready to help, we must guard against the seduction of our free will by the snake, the Devil, working through worldly pleasures such as delectable foods, fine clothing, personal power, vain possessions, and excess comforts. Thus Christ teaches us that we must ask only for "bread," namely, the necessities of life and no more, and that we must concentrate on spiritual blessings according to his words: "Seek first the Kingdom of God and His righteousness, and all these things will be added to you" (Mt 6:33). St. Gregory puts a strong emphasis on justice, insisting that the "bread" for which we toil must be a "bread of justice," that is, gained from honest and godly labor, not from the groans and tears of others.

The last discourse takes up the petitions, "Forgive us our debts as we forgive our debtors," and, "Lead us not into temptation, but deliver us from the Evil One." The theme of forgiveness is interpreted from the standpoint of St. Gregory's favorite teach- ing, likeness to God. For St. Gregory, nothing expresses the greatness of God's love and generous mercy as does the divine attribute of forgiveness. By being forgiving, men and women can attain to God's likeness and become, as it were, "gods" by shar- ing in God's attributes. St. Gregory contemplates the enormous debts we owe to God as a fallen humanity -- deserting our place in paradise, defacing God's image in us, and committing all manner of sin through the outward senses as well as from within the heart. He calls the conscience to full awareness in order not to resemble the unmerciful servant who was forgiven a mythical sum and yet abused his fellow servant who owed him a small amount (Mt 18.23-35). In an interesting passage, St. Gregory warns mas- ters to treat their slaves with patience because, among other things, the distinction be- tween masters and slaves was by way of human custom and law, not by God and creation.

On the subject of temptations and the Evil One St. Gregory is unusually brief. Certainly he could have said much more, especially about the difficult idea of God "leading" people into temptation. This particular element has been interpreted in two main ways, either that God should not "allow" us to enter into temptation, or that God Himself should not "test" our faith by means of trials because we might fail the test due to hu- man weakness. Perhaps St. Gregory assumes the former. For him, temptations and the Devil are equated. Temptations are "the evils of daily life." They arise from our preoc- cupation with the things of the world which is under the power of the Devil (1 Jn 5:19). The decisive answer is to remove oneself from worldly preoccupations, yet not neces- sarily from the world itself. Thus St. Gregory ends his meditations on the Lord's Prayer by lifting up once again the ascetic vision of Christian life reminiscent of Christ's words: "Enter by the narrow gate; for the gate is wide and the way is easy, that leads to de- struction, and those who enter by it are many. For the gate is narrow and the way is hard, that leads to life, and those who find it are few" (Mt 7:13-14).